This is a little different than my normal blogs/reviews, but I thought it might be fun to write this out regardless. I don’t think I’ve written about what I do before besides my freelance editing, but surprisingly (or not) I read a decent amount for my regular job too. I teach English Language and Literature in from 8th to 12th grade. As such, it should come as no surprise that I value reading, and that I also value teaching students how to read. For me this isn’t necessarily teaching students the practical aspects like vocabulary, sentence structure, etc. that are needed to even begin, although these are obviously extremely important, but rather teaching students how to enjoy reading and how to get more out of it. I’ve been extremely lucky in the students I have had the opportunity to teach, but that does not mean that they have all had an inherent love of reading either before or after my class (but I hope they liked it at least a bit more afterwards).

I’ve seen this article bouncing around many of the online communities I’m in, and the problem it talks about got me thinking—and now writing. If you are short on time, the gist is that students at Columbia University struggle to read a book because… they’ve never had to read a whole book before. Not only do they struggle to read a book in its entirety, but they more often struggle to “attend to small details while keeping track of the overall plot,” they have “a narrower vocabulary and less understanding of language,” and they are “less able to persist through a challenging text than they used to be.” These don’t sound like problems that only affect the lit majors at an Ivy; these sound to me like students who will face increasing difficulty regardless of their choice of major or career.

Many schools are moving towards a curriculum that uses excerpts instead of full novels; students like those in the article never have to read a book by the time they graduate. There is a continuing push towards STEM fields, relentless pressure for students to be “career-ready,” and, of course, the never-ending problem of preparing for the standardized tests. Where is the room for a whole novel when students have to deal with all of this? I could understand that argument for students in high school who are preparing for specific majors in university that have to dedicate more time to whichever subject fits their needs, but in middle school? Elementary? Reducing the entirety of K-12 education to career prep for business and tech majors is criminal; shouldn’t we be giving them more than this? The humanities aren’t for everyone, but neither is finance.

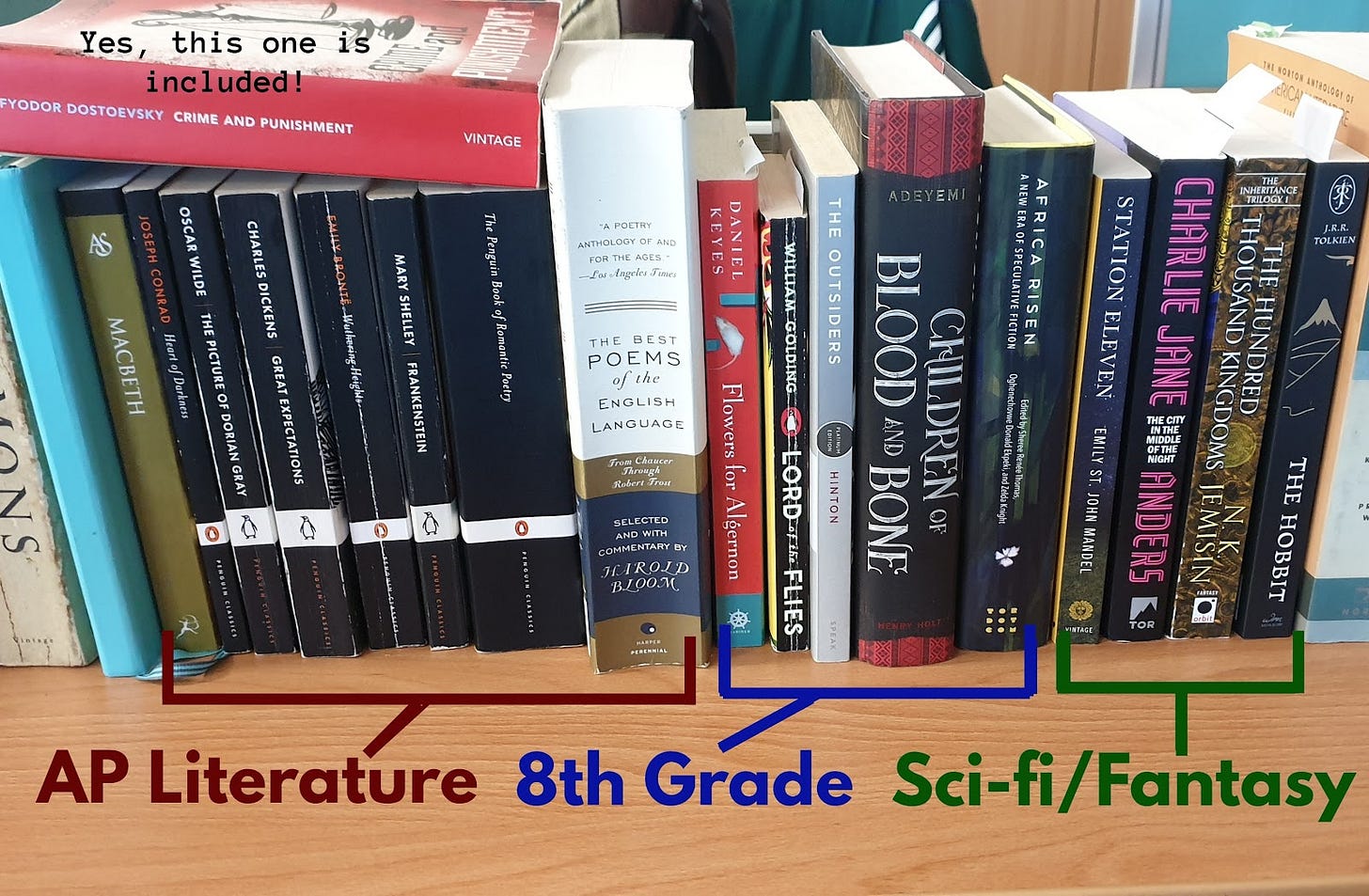

Ok, I’ve gone on way too long making this sound like a practical argument for reading when that’s not my main goal (but really, everyone should read). What I really want to stress is that reading is, and should be, rewarding. Reading allows us to experience what would never be possible in our own lives, to connect to others across time and space, to lose ourselves in the life of another if even for a short while. Also, reading is fun! Even hard books; I mean it. My current book list for my 12th graders is full of classics, but we have some awesome discussions in that class. Ah, maybe that’s part of it, I don’t do tests, at least not for the novels I actually want them to read. I don’t have reading quizzes to make sure they finished the chapter, and I don’t make the students spend their time on assignments designed to prove they “did the work.” We read novels, poetry, and short stories, and then we talk about them. Sure I guide discussion to make sure we hit a few key points, but it’s not uncommon to go off on a tangent for fifteen minutes. This isn’t to say the students in my class don’t write, because they do (sometimes too much according to them), but I want them to like the books. I want them to read a poem and just get into it. I want them to experience some of the best that literature has to offer without it being ripped apart by analysis, without academic jargon and over-analysis destroying what pleasure they could have had. Crime and Punishment is an awesome story, and even better when you’re not stuck answering multiple-choice questions about the narrator. Students have deep insights on their own when you give them time to sit with John Keats or William Blake.

I teach literature because I love reading, and the primary goal for my teaching is that my students will also love it. They don’t need to like the books I do, and they don’t need to have the same interpretations even if they do. I want to show them a few of the things I like, perhaps some I don’t (don’t tell them!), and hope that something sticks. We’re on a search for meaning, in the books and in ourselves. They’ll be better at writing essays by the time we’re done, and, even if our discussions tend to be rather free-form, they’re going to be a hell of a lot better at literary analysis too.

I was reading through the comments on a Reddit thread (I know, I know…) on r/Teachers about an instructional coach who was advising (forcing?) the teachers in this district to stop assigning novels. Happily, most teachers in the thread were outraged. Unhappily, I saw the following comment thread about novel appreciation:

Part of me seriously doubts someone could/would get through all of Moby Dick and have nothing else to say, but let’s just pretend people tell the truth online. Now, not seeing past the surface layer of a story is one thing, but to argue that authors should just directly write whatever meaning they are trying to get across? I mean, first off, that’s not how transmission of meaning works. That’s not even how language works! All language is metaphorical, a representation of the original. If you want to just know what Moby Dick is about, I’d have to just put you on a boat with Ahab and Ishmael so you could experience the attempt to catch a whale, but even then you wouldn’t have the same experience as either of those characters so we’ve lost meaning that way too. If I told a group of people that a guy was on a boat hunting a whale, I doubt the images in their minds would be the same. Language already is an interpretation of reality, but what makes it beautiful is that we can do so much more with it. I will admit that even I don’t like when authors are purposefully difficult, hiding most of the meaning behind ridiculous vocabulary, obscure references, and a daunting number of pages, but if those things happen because there really isn’t another way to say the entirety of what they mean, then it’s often worth it.

Students aren’t going to start with Moby Dick, or at least I hope not, but how do you encourage them to open their minds to the possibility of other experience? How do you show them the possibilities that literature allows? My students don't come to me in 8th grade with mind-blowing analysis skills, but they can definitely tell me what they think a story means. We work together and build on what they have. I start with short stories, help them develop their own readings of the text as we go, then show them a few other lenses after they’ve established their own thoughts, but I want to encourage them to try to read all of their stories through multiple lenses. There is validity in personal interpretation as long as you can back it up with the text. This doesn’t mean basing interpretations on textual evidence to the extreme that there is nothing but the literal, but I do try to develop their skills in reading for detail, reading carefully. Students will usually have a hard time reading for more than what's on the page unless you show them that is an option, even the preferred option.

We don’t only do this with fiction; reading nonfiction for literal meaning is also an important skill, but understanding layers of language and being able to interpret multiple meanings is important across all genres. Even if we skip over figurative language, knowing an author's purpose can completely change the meaning of a text. To return to my earlier digression, this is true even if you aren’t going into the humanities for your degree or career. Resisting this (like the Reddit user above or countless others you can find online or in real life) because of some image of an academic pastime where elitist snobs are overanalyzing in their ivory tower may have some validity, but I doubt the people who generally argue against literary analysis/interpretation are actually reading academic and literary journals and critiquing the latest hot takes on Milton.

Why limit ourselves to only being able to understand the literal and straightforward? Even if you’re not reading for social commentary or political critiques, don’t you still want a story to be good? To be great? And let me tell you, the more depth a work has, the more potential it has. Let’s go for a broad audience for a minute and talk about superheroes (even though Marvel and superhero movies in general are clearly in a downward spiral). Where’s the fun in discussing the MCU if all we get is “The superheroes beat the bad guy, the world is saved!”? If that’s all they really had to say in the 11 years and 23 films it took to finish phase 1, why didn’t they just cut it down? Answer: because there’s a lot more to the story than the basic, literal explanation of what happened.

I think the story gets a lot better if we can discuss things like Iron Man’s character arc from a greedy, narcissistic playboy who profits off of war, to a man who uses his power (wealth, intelligence, etc.) to protect those he loves, even at the cost of his own life. Sure, the movies look cool—we love explosions and shiny metal suits—but a big part of what brought Marvel success was that they wrote good stories. A good story isn’t just stuff blowing up, it requires strong pacing, compelling character development, interesting settings, maybe conflicts that the audience can identify with in some way. You can’t do this without knowing how stories work, and you don’t know how stories work unless you read, specifically fiction, and read well.

So, getting back on track, what does it mean to read well? I don’t think there’s just one way, but I do think that all of them require a love of reading in some form, and you won’t develop a love of reading without doing it. Unfortunately, to find what you love to read, you are likely going to have to read many things you don’t love as well. That’s how you find which sports you like, what your favorite food is, which bands are worth listening to on repeat, and this also applies to books. I’ve had students come out of my class with a surprising fondness for 19th c. Russian literature. I’ve also had students leave without finding a new genre they are passionate about, but they are even more sure about their love for Wattpad romance. I’m not telling them what they have to like, I’m just trying to help them find it and, when they do, enjoy it at a deeper level.

I am lucky that I can teach six novels in a year to my 12th graders, but even for those who love reading, they had to build up to this. They didn’t start elementary, middle, or high school being able to read this much for one class, regardless of the difficulty of the text; they had to grow. I am also lucky enough to teach 8th grade and have a say in the curriculum, making sure my students are reading full novels throughout both middle and high school. The ones who do best have read novels before they get to me. These students also do better with every form of writing that I teach. They are also generally stronger with poetry, short fiction, and nonfiction reading. You should hear the conversations we have, even in the 8th grade class. Just give them a chance and students will blow you away with the depth and maturity of their reading. From what I’ve seen, the students who read get into more and higher-ranked universities than the students I’ve met who, like the ones in that article, never had to read a full book. I think it's unlikely the majority of Columbia admits can't read a novel.

I make my students read because it matters in so many ways. If the pragmatic outcome is what’s important to you, then you should be reading. If you want more insight into whatever popular media you enjoy, then you should also be reading. Most importantly, if you want to grow intellectually, experience perception beyond the borders of your own mind, stretch your imagination and understanding to their fullest, then you should definitely be reading.